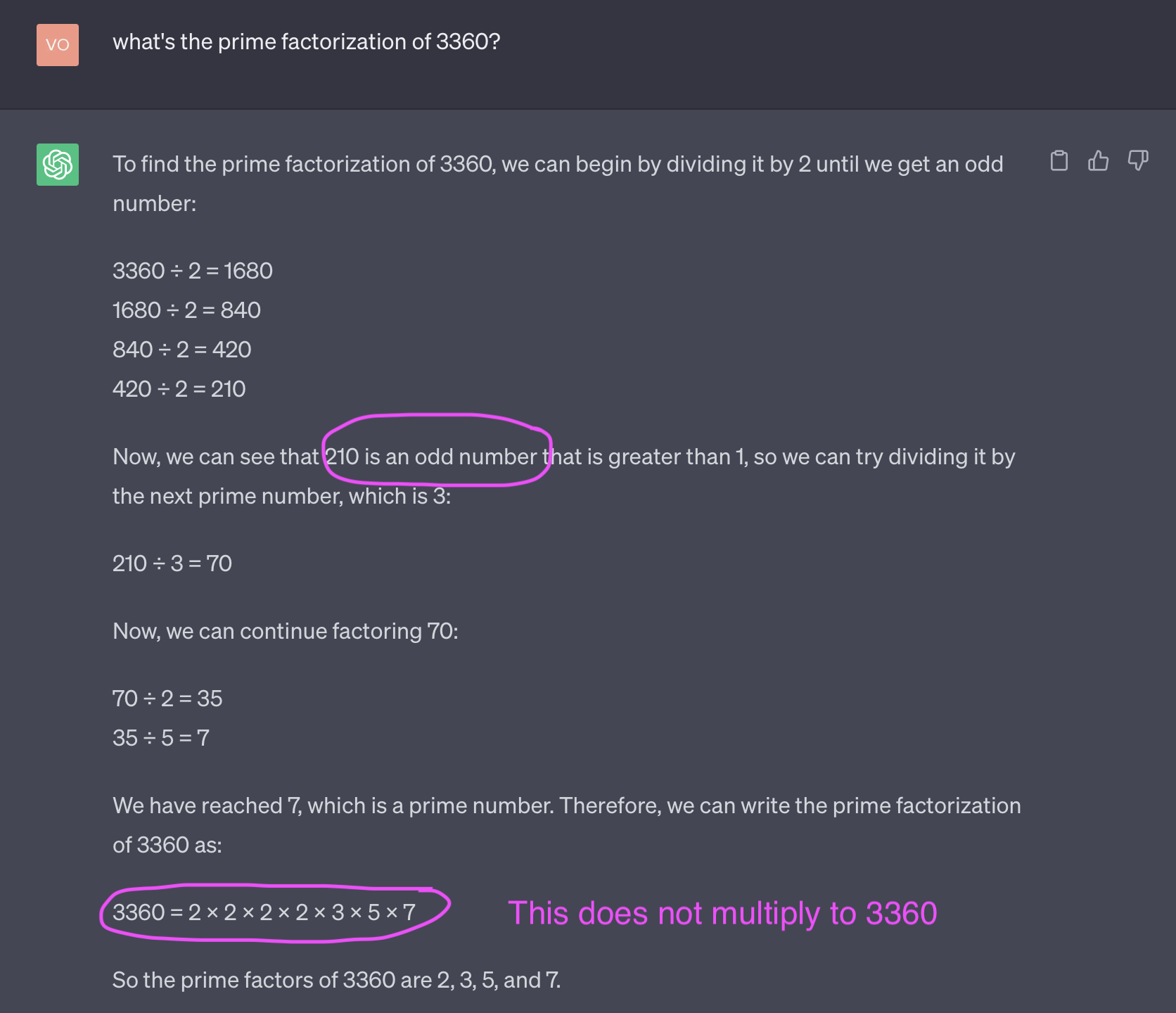

The conversation around regulations for AI had started years ago. With the latest buzz and chatter around the GPTs roaming around performing miracles (or so advertised) and failing equally spectacularly (e.g., it told me that 210 is an odd number and couldn’t figure out the prime factorization of 3360), all at the same time creating another wave of layoffs coupled with “human extinction risk“, it’s no surprise that how these advancements are to be used would come under scrutiny.

The Three Types of Errors In Policy Making

The purpose of regulations (policy more broadly) is to create usage safeguards (for consumers, businesses, economies, etc.) without crushing innovation and competition.

Every time there is policy put into place, there will be three main types of errors introduced into the system it affects. These errors are Type I (false positive): when someone or something is under the regulatory lens when it shouldn’t be; Type II (false negative): when someone or something is not under the regulatory lens when it should be. And the third type, “the error of unintended consequences”. Note that a lack of codified policy is still a policy.

A hallmark trait of poor policymaking is intolerance for a certain type of error. If we want to make sure that there is never a false negative (excluding something from regulatory oversight when it should have been), it’s easy to do. Just lazily say that every computer program needs to be audited and certified by an anointed certification body. This is, of course, stupid. The Type I error would become extraordinarily high. We can also say that we never want to make a Type I error (including something for regulatory oversight when it isn’t necessary) by having no rules whatsoever. This will induce very high Type II errors and chaos.

Good policy aims to minimize Type I and Type II errors as much as possible without kneecapping growth or creating chaos. Unintended consequences are unintended; and thoughtful policymakers would do their best to account for “creative” human behavior.

AI regulation is going to make all three of these types of mistakes. Type I and Type II errors will lead to more nuanced language to include and exclude those which were falsely excluded or included, respectively. There will also be many unintended consequences. Black markets being one of them (a “known” unintended consequence).

Understanding AI Use Cases and Risk

On one end of the risk spectrum is AI-controlled weapons of war and destruction. We have drones for war already. Robot dogs for law enforcement are here, too. It’s not too much of stretch for them to autonomously work toward a military objective. Self-organizing bots already exist. Getting global regulation wrong on AI-controlled weapons of war (Type II error, false negative) would be disastrous.

On the other end of the risk spectrum is, for example, an AI recommendation (and purchase!) engine for the next book I should read. Sure why not, so long as I can set a monthly budget.

And everything in between is various shades of gray. Probably benign is your AI coffee machine.

How much regulatory burden should the above two products have to deal with? They would be Type I (false positive) errors if the AI regulatory burden is relatively high.

Self-driving vacuum cleaner for my home? Oh that’s been around for a while with barely a blip of consumer concern (other than potential privacy issues about the blueprint of one’s home being transmitted back to the manufacturer). Probably a Type I error; the data privacy and protection stuff would fall under those respective laws.

AI + Medicine? Yeah … regulate away.

That cool tech productivity app that uses generative AI so you can finish another slide deck more quickly? Whatevs.

Automated loan approvals based on a questionnaire? Probably a Type II error to exclude such a use case. Not that such a product shouldn’t exist, but that such a product should probably have to meet some regulatory approval standard to address concerns on discrimination, bias, and algorithmic transparency.

Self-driving cars where the passengers can just nap? That’s a hard no for a lot of folks without some serious updates to regulations, testing, certifications, liability and insurance laws, transportation infrastructure, mandated maintenance (not just the physical parts or running the vehicle, but also the onboard computer and computer vision system), vehicle inspections, etc. Type II error, hands down if the AI regulatory burden is not high enough.

Computer-controlled airplane landing? Um, that’s already happening. I was on a flight many years ago when upon landing, the pilot announced over the PA system that the landing was done completely by computer. But it wasn’t called AI!

And that’s the rub.

SALAD?

Let’s recognize that AI is a marketing term. I’m old enough to remember when linear regression was part of data modeling. Then came machine learning as the buzz word. If you had a product that did anything to customize an experience, you were doing machine learning. And now linear regression is machine learning. We’ve also had the “smart” prefix. Smart phones. Smart toasters. The devices were not just preprogrammed automatons. Their behavior was to change and adapt to your patterns.

We’ve arrived at AI. Using a neural net? Then you’re doing AI! Oh wait, you are using a logistic regression as a classifier for your discriminator to help with adversarial training of a generative solution? AI. Oh, you are predicting something? AI. Chatbot? AI. Autofill? AI. Autocorrect? AI. Hidden Markov Models? AI. High school Algebra problem solver? AI. High School Algebra tutoring program? AI.

When everything is AI, then nothing is. And the term will be dead. On the other hand, if anyone who says that their product is an “AI” product, is subject to regulatory burden, then regulation just may kill the term and give birth to a new term. This would be an example of policy indexing on reducing Type II errors to zero at the expense of Type I errors.

Good policymaking will properly and appropriately define what AI is and which use cases need further scrutiny. So you can have your AI coffee maker and know that it’s just a marketing term, but at the same time, be assured that your coffee maker isn’t going to start thermonuclear war to meet its objective of securing the last shipment of Kona coffee.

If we start seeing terms like “integrated statistics” or maybe “SALAD” — Statistics, Automation, Linear Algebra, Data — and people selling SALAD solutions, then we know that AI policymaking got bungled along the way.

While you’re here. I sell SALAD. Interested in any?